A fresh wave of optimism about extraterrestrial life is emerging from an icy ocean world orbiting Saturn.

A major milestone in the search for life beyond Earth has just been reported. In a study published in Nature Astronomy, scientists present new evidence suggesting that Enceladus—Saturn’s frozen moon—could potentially support life beneath its thick ice shell.

Researchers from the University of Stuttgart (Germany) examined microscopic ice grains that are blasted into space through cracks on Enceladus’ surface. Using archived NASA Cassini data collected over more than a decade, the team found that these particles contain complex organic molecules—a strong indication that Enceladus may meet many of the key requirements for habitability.

“We believe the organic molecules detected in the Cassini dataset could contribute to the formation of biologically relevant compounds,” said Dr. Nozair Khawaja, the study’s lead astrobiologist, in comments to ScienceAlert. “This significantly increases the likelihood that Enceladus could be a habitable environment.”

The Hidden Clues Inside Space Ice

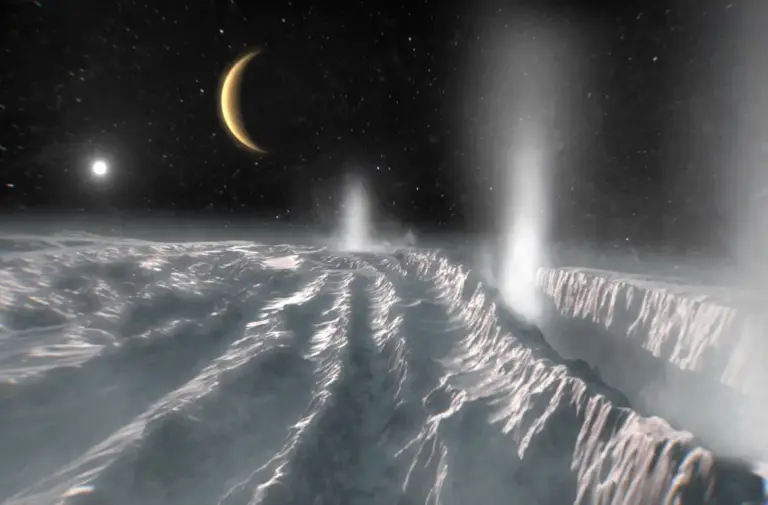

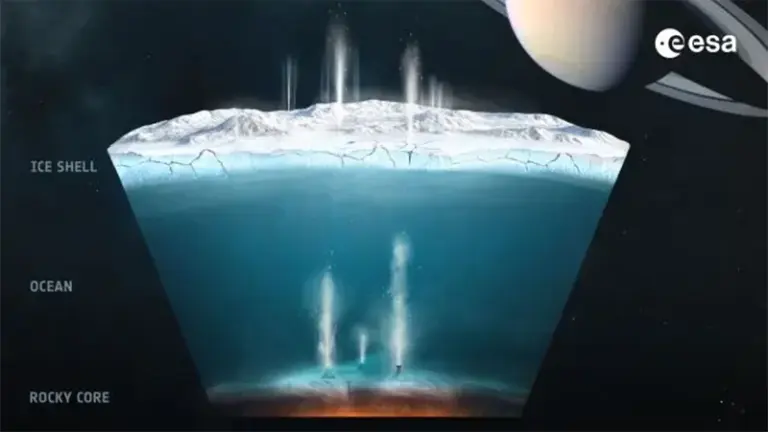

With an average temperature around –330°F (–200°C), Enceladus appears utterly inhospitable at first glance. But in 2005, scientists discovered strong evidence of a vast subsurface ocean under its icy crust—most clearly shown by towering plumes of water vapor and ice erupting from fractures near the moon’s south pole.

During its Saturn mission, Cassini collected many ice particle samples using the Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA) while flying through the planet’s rings. However, many grains in the rings may have formed centuries earlier, raising concerns that long exposure to space radiation could have altered them.

That changed in 2008, when Cassini performed a daring fly-through directly into Enceladus’ active plume—racing through the “spray” of water vapor and ice at roughly 64,800 km/h. This maneuver delivered far cleaner, more reliable chemical signatures than earlier sampling.

Dr. Khawaja explained that the high impact speed was crucial. At lower speeds, ice fragments and the signals of organics can be masked by clumped water molecules. At extremely high speeds, water molecules don’t have time to recombine in the same way—making previously hidden organic signals easier to identify.

What the Team Found and Why It Matters

Using advanced analytical methods, the Stuttgart group identified multiple newly recognized compounds originating from Enceladus’ interior ocean, including:

- Aromatic compounds (ring-shaped organics)

- Ethers (volatile organics with distinctive chemical behavior)

- Traces of nitrogen–oxygen–bearing compounds

- Additional elements and signatures not clearly reported before

Importantly, the chemical profile supports the idea that the material Cassini detected in Saturn’s rings came from inside Enceladus, rather than being produced by radiation-driven reactions in space.

When these new results are combined with earlier Cassini findings—such as salts, hydrogen, and phosphate—researchers note that Enceladus appears to contain at least five of the six commonly cited basic ingredients for life. The only major element not yet confirmed is sulfur.

“We’re confident these molecules originate from the subsurface ocean beneath Enceladus,” Khawaja wrote in an email to ABC News, adding that this strengthens the case for a potentially life-friendly environment on the moon.

While none of the detected compounds can yet be proven to be biological in origin, the team argues they may serve as precursors—building blocks within chemical pathways that could eventually lead to living systems.

A Hydrothermal World Like Early Earth?

The conditions inferred on Enceladus resemble hydrothermal systems on Earth’s seafloor—environments widely believed to have played a crucial role in the emergence of the planet’s earliest life billions of years ago.

On Earth, deep-sea vents generate organic chemicals such as methane, ammonia, and complex carbon chains, providing energy and raw materials that support microbial ecosystems. Finding comparable chemistry on Enceladus is exactly the kind of signal that excites astrobiologists.

“If Enceladus’ ocean operates like Earth’s hydrothermal systems, then the possibility of life is entirely plausible,” Khawaja emphasized. “The richness of organic chemistry on a water world beyond Earth is truly extraordinary.”

He also noted that Cassini’s dataset still holds many unanswered questions: ongoing analysis may reveal even more discoveries.

What Comes Next: Future Missions and Rising Momentum

These findings have energized the international scientific community. The European Space Agency (ESA) is reportedly considering long-term plans for a mission that could land on Enceladus in the coming decades, aiming to directly sample the surface and plume material.

Meanwhile, NASA’s Europa Clipper mission is already underway—heading toward Europa, Jupiter’s ice-covered moon and another leading candidate in the search for life. Like Enceladus, Europa is believed to host a subsurface ocean, along with geological activity that could provide energy sources essential for life.

If either moon ultimately yields evidence of microbes—or even early signs of primitive biology—it would rank among the most profound scientific discoveries in human history.

For now, the Stuttgart team’s work not only deepens our understanding of Enceladus, but also expands the map of where life might exist beyond Earth. From a small frozen moon, Enceladus has become one of the strongest hopes in the quest to find life in the cosmos.