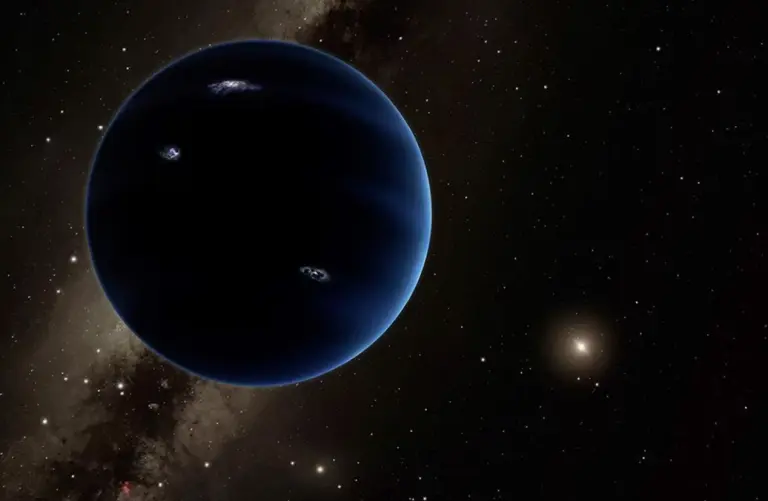

A yet-unseen planet may be lurking in our Solar System—quietly orbiting the Sun in the deep, frigid darkness far beyond Neptune. In a new study, researchers propose a fresh candidate they’ve nicknamed “Planet Y.”

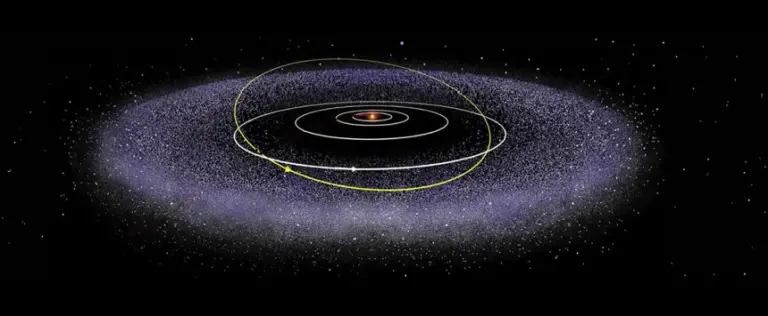

Unlike a typical discovery confirmed by telescope images, Planet Y is inferred from an odd pattern: the unusual tilted orbits of multiple distant objects in the outer Kuiper Belt—the cold region of icy bodies beyond Neptune’s path.

The team argues that something is disturbing these orbits, pushing them into an unexpected slant.

“One plausible explanation is a hidden planet that has not been directly observed—smaller than Earth but larger than Mercury—moving through the most remote part of the Solar System,” said Amir Siraj, an astrophysicist at Princeton University.

He stressed that the study does not claim a confirmed planet: “This paper is not the discovery of a planet. It’s the discovery of a puzzle—and the most reasonable solution to that puzzle could be a planet.”

The research appears in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters.

From “Planet X” to “Planet Y”: A Century-Long Search

Planet Y is the latest in a long line of “missing planet” ideas tied to the Kuiper Belt—the same distant zone that contains Pluto, reclassified as a dwarf planet in 2006.

This region is extremely hard to study: it’s far away, dim, and crowded with faint icy objects, making direct observation challenging. That may change soon, thanks to the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which is preparing a 10-year sky survey.

Siraj believes answers could arrive quickly: within the first two to three years of Rubin’s observations, the hypothesis could be tested. If Planet Y sits within Rubin’s detection range, astronomers may be able to spot it directly.

The “hidden planet” idea has deep roots. After Neptune was discovered in 1846, astronomers suspected there might be yet another planet beyond it. In the early 1900s, the term “Planet X” was popularized by astronomer Percival Lowell, who thought orbital irregularities in Uranus and Neptune suggested an unseen object.

When Pluto was found in 1930, some believed Planet X had finally been identified—but Pluto turned out to be far too small to explain the supposed gravitational effects. Later, Voyager 2 data in the 1990s refined Neptune’s mass estimates, removing much of the earlier “need” for an extra planet.

Interest reignited in 2005, when astronomers—including Mike Brown (Caltech)—discovered Eris, an icy object slightly larger than Pluto. That finding fueled the debate that ultimately led to Pluto’s downgrade.

Then in 2016, Brown and colleague Konstantin Batygin proposed “Planet Nine”: a body estimated at 5–10 times Earth’s mass, orbiting extremely far out—around 550 times the Earth–Sun distance.

Siraj notes that Planet Nine and Planet Y could both exist, representing two separate hidden worlds at the Solar System’s frontier.

A Strange Tilt in the Outer Solar System

The Planet Y idea began when Siraj investigated whether the Kuiper Belt is truly “flat” in the way standard models predict.

The Solar System’s major planets have slight orbital tilts, but overall they lie close to a shared plane—often compared to grooves on a vinyl record. By that logic, distant icy objects beyond Neptune should follow roughly the same pattern.

Instead, the team found an unexpected feature: beyond roughly 80 times the Earth–Sun distance, many of these objects show an average tilt of about 15 degrees.

“That 15-degree misalignment is what triggered the Planet Y hypothesis,” Siraj said. The researchers explored other explanations—such as a passing star or details of the Solar System’s early formation—but concluded a hidden planet best fits the data. If an external event caused the tilt long ago, they argue, the effect should have faded by now.

To test the idea, the team ran computer simulations that included all known planets plus an additional hypothetical world. They varied the parameters repeatedly to see which setup matched the orbital patterns most closely. Their results suggested Planet Nine alone doesn’t explain the tilt—and that a different planet may be needed.

What Planet Y Might Be Like

Based on the modeling, Planet Y could have:

- A mass somewhere between Mercury and Earth

- An orbit around 100–200 times the Earth–Sun distance

- A tilt of at least 10 degrees relative to the main planetary plane

Right now, astronomers can only infer this possibility from the orbits of around 50 extremely distant objects, so the evidence is not yet definitive.

The Rubin Observatory Could Settle the Debate

Once the Vera C. Rubin Observatory begins full operations in Chile (expected in the coming fall), the situation could change dramatically. The telescope—installed at an altitude of 2,682 meters and equipped with what is widely described as the world’s largest digital camera—will repeatedly image the sky, potentially surveying the entire visible region on a rapid cycle.

Even as a hypothesis, Planet Y is already injecting new momentum into planetary astronomy—raising the possibility that a mystery debated for generations may finally be resolved.

And if future observations confirm it, the Solar System’s map may expand again—adding a lonely, icy world on a distant orbit: Planet Y, circling the Sun far out in the cold, dark margins of space.