Astronomers have reported what appears to be the first rogue (free-floating) planet with both its distance and mass pinned down directly—a major step forward for studying these elusive worlds. The object is roughly Saturn-mass and lies about 9,950 light-years from Earth, in the direction of the Milky Way’s central bulge.

What is a “rogue” or “free-floating” planet?

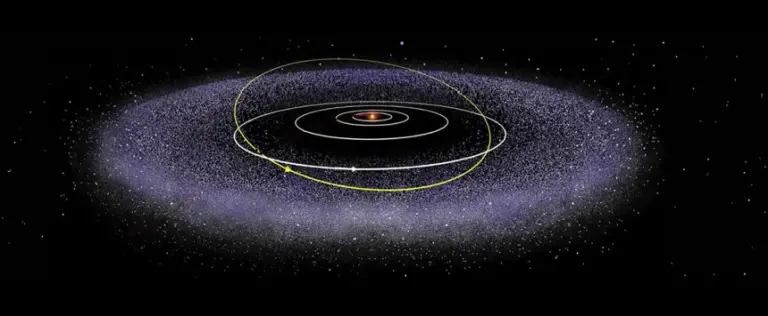

Most planets form in protoplanetary disks and remain bound to a star. A free-floating (rogue) planet is different: it drifts through interstellar space without orbiting any host star—at least not closely enough to be gravitationally “attached” in the normal planetary sense.

Scientists have suspected for decades that the Milky Way could contain huge numbers of these lonely worlds, potentially comparable to—or even exceeding—the number of stars, but confirming individual objects has been extremely difficult.

How this planet was found (and why this detection is special)

The key technique: gravitational microlensing

A rogue planet is usually too faint to see directly. Instead, astronomers detect it through gravitational microlensing: if the planet passes almost exactly in front of a distant background star, the planet’s gravity bends spacetime and acts like a lens, briefly magnifying the star’s apparent brightness.

Microlensing events are typically “one-off” alignments—there’s no guarantee they’ll repeat—so teams run high-cadence sky surveys to catch them in real time.

Event name(s) and who observed it

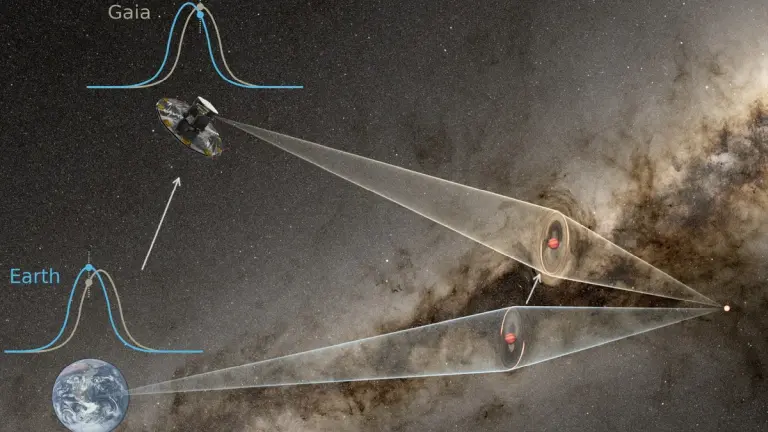

This event carries two survey designations: KMT-2024-BLG-0792 (from KMTNet) and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516 (from OGLE). It was observed from the ground and by ESA’s Gaia spacecraft, which provided the second viewing geometry needed to solve a long-standing problem.

Breaking the “mass–distance degeneracy” with parallax

Historically, microlensing often can’t uniquely tell you the lens’s mass because the light-curve shape can be reproduced by different combinations of mass and distance (the “degeneracy” problem).

What changed here is that the event was seen from two separated vantage points (Earth and Gaia). The slight differences in timing/shape between those observations reveal the microlensing parallax, which lets researchers triangulate the distance and then derive the mass more directly.

What astronomers think it is: Saturn-mass, likely ejected

The team’s modeling indicates a lens mass of about 0.22 Jupiter masses, which is roughly ~70 Earth masses—close to Saturn’s scale (Saturn is ~95 Earth masses).

Crucially, the object is interpreted as either gravitationally unbound (a true rogue planet) or on an extremely wide orbit around a star (so wide it behaves much like a free-floater observationally).

How do planets become “rogue”?

Current thinking includes three main pathways:

- Dynamical ejection: In the chaotic early stages of a planetary system, close gravitational interactions between giant planets can fling one outward and eventually eject it entirely.

- Stellar flybys: A passing star can destabilize a system and strip planets away.

- Star-like formation (less favored here): Some free-floaters could form directly from collapsing gas clouds (more like brown dwarfs), though this study argues the object more likely formed in a disk and was later ejected.

Why this matters: the Milky Way may be packed with “lonely worlds”

Because this measurement ties down both distance and mass, it becomes an anchor point for population estimates. The broader implication is that rogue planets may be common, and that planet formation/ejection could be a routine outcome of building planetary systems.

What’s next: Roman and China’s Earth 2.0 (ET)

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope

Roman is expected to be a game-changer for microlensing surveys: NASA notes Roman’s field of view is ≥100× larger than Hubble’s, allowing it to survey the sky ~1,000× faster with similar sensitivity in the infrared. NASA’s current public schedule targets launch by May 2027 (some older coverage cites 2026).

China’s Earth 2.0 (ET) mission

China’s Earth 2.0 (ET) mission is designed to study exoplanets using both transits and microlensing, and explicitly includes goals related to the origins of free-floating planets.

Publication

The results are reported in a paper titled “A free-floating-planet microlensing event caused by a Saturn-mass object” (authors include Subo Dong and Andrzej Udalski), with broad press coverage noting publication in Science on January 1.